Imaginative bilingual books like Patricia Brady-Danzig’s Fabrizio’s Fable – La Favola di Fabrizio, can be powerful allies for foreign born parents. Especially in a country like the United States where Italian, my native tongue, is not widely spoken.

So, when Patricia approached me for a possible feature, it was a no brainer. But what made the experience more interesting was to find myself trading field notes with her: anecdotes from her public readings versus my own adventures raising a bilingual child.

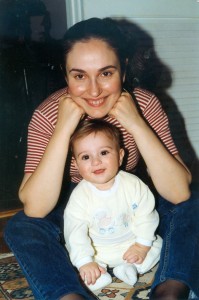

Since the day my son Matthew was born, I knew that I wanted him to be bilingual. I couldn’t bear the thought of him not understanding my language for a number of reasons. First of all because it was the only way he could communicate with my “No-Speak-English” Italian parents. But I also felt strongly that, one day, he could understand the side of me that after moving to the States refused to be lost in translation.

I was ready. I would speak to Matthew in Italian at all times, and he would learn to speak it like a native.

There was only one flaw to my master plan: Matthew’s interest in doing it.

He began to talk when he was about two-years-old and, to my disappointment, while he seemed to possess a well-honed listening comprehension of my mother tongue, he showed absolutely no desire to express himself in it.

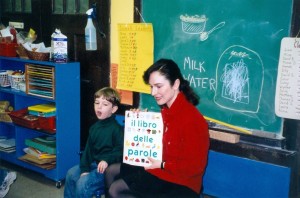

Putting my best foot forward in Matthew’s pre-k class, when I was invited to teach the kids some common Italian words

In fact, he would remark, “Why do I have to speak Italian?” Or remind me that this was “America” (of course pronounced with an American accent) and people didn’t speak Italian. (The audacity of these little people!)

Well, “it’s my language” I would explain, and “it would be nice, when you go visit the nonni, to be able to speak with your friends.”

Hmm, I could tell that that went far…

Then, there were his attempts to show appreciation of other world cultures. Like the day when he came back from kindergarten to share with me that he had learned to count to ten…in Spanish. (Argh!)

The daredevil knew which buttons to push.

For years we performed a relentless duet of Italian-speaking-mom and American-English-speaking (unyielding) child. People would notice us at bookstores, ice cream parlors, at the park. They would observe us, become infatuated with figuring out what language was I speaking and, not infrequently, displaying the utter lack of observational skills that would add insult to injury.

“What language is that?” they might ask.

“Oh, it’s Italian, how wonderful,” a typical reply would be. To then kill it off with, “does he speak it too?”

I was always polite and pointed out the obvious: he did not, YET. But he understood it perfectly, which of course meant that speaking it wasn’t too far away. (I never explained the “will” factor. It was enough already.)

Inside though, the roaring thunder of my frustrated thoughts sounded very different.

“You, imbecile!” I would have loved to pounce (At least I could have taken it out on someone.)

“What sort of a question is that? You’ve been sitting there, eavesdropping for a half-hour and my son didn’t say a word of Italian?

Does it seem to you that he speaks it?”

But I never did. I knew that the occasional observer of my family’s bilingual vignettes couldn’t understand how sensitive a topic that was for me. Matthew and I probably seemed playful, we turned on people’s curiosity and they wanted to know more about us.

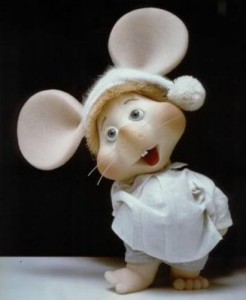

It wasn’t until I brought home Topo Gigio, though, when Matthew was in first grade, that I decided I had to do something about my son’s unmitigated bilingual-resistance.

At the time, I was working for an Italian television channel in Fort Lee, N.J., when our marketing department handed out props from some of the shows we distributed in the States.

One of them was a toy watch with Topo Gigio’s face, Maria Perego’s famous television puppet from the sixties and seventies. Surprised to find one of my childhood characters, I brought it home to show it to Matthew.

“What is that?” he asked dismissively.

“It’s Topo Gigio,” I replied excited and utterly undeterred, “an Italian mouse that used to be on TV when mommy was a little girl.”

Matthew looked at me as if he couldn’t understand what the big deal was. Then, he deadpanned, “Mom, Mickey Mouse is a lot more famous!”

Huh, the little monster. I couldn’t believe my ears!

“Oh, yeah,” I said to myself. “’Mickey Mouse is much more famous,‘ eh! We’ll see about that.”

Fired up and unwavering in the face of adversity, I talked it over with my family (what do we do?). We devised a plan of action. The following summer, when Matthew would turn seven, I would leave him with my parents, by himself, for the whole school vacation. He would be, of course, in full English mode by the time I drop him off.

Matthew holding a toy sword poses with his Italian friends in my parents’ garden during one of his summer-immersions in Perugia

As it turned out, I too knew what buttons to push (ah, I had to admit, the apple probably didn’t fall too far from the tree…)

By the time I picked him up toward the end of August, almost three months after he had arrived in Perugia, Matthew was not only fluent in Italian, but could also speak some Perugino, the local dialect.

Hurray! Victory at last.

It did help that if he wanted ice cream he had to ask for “gelato,” or if he wanted to play with his friends Arianna, Marco or Andrea (a boy’s name in Italian) he had no choice but to speak in Italian.

The good new is that all along, it was in him. All those years of speaking in my mother tongue, pouring Italian words into his ears, had paid off! Immersing him in an environment where English couldn’t come to the rescue did the rest.

Matthew has spent every summer at his nonni’s home, in Umbria, ever since. He has now graduated college and lives in Italy, delighted by his bilingual, bicultural world.

All this is to make the point that good literature, cultural immersions, and just sticking to your guns, it all helps. Be consistent, but be considerate, don’t force the issue, but persevere. And above all, be creative.

To further prove it, I’ll share a story about Brady-Danzig’s experiences reading Fabrizio to very young audiences. At one event she was confronted by the discontent of a little boy, Max, who said to her “I hate Fabrizio! I don’t like stories with animals. I like space stories.”

Matthew gives a speach in Italian while my sister Simona looks on, at a family function last year in Assisi, Umbria

“Hmm,” pondered the author, who then decided to pick up a children’s book about spaceships.

She contacted the school and asked permission to show it to Max. He liked it a lot, but confirmed, “I don’t like Fabrizio.”

“That’s ok, Max,” she reassured him. “But what if Fabrizio went into space?”

“Oh,” marveled the boy. He then looked at the writer and replied, “Yes, I like that.”

Print This Post

Print This Post

Comments for: Topo Gigio, Mickey Mouse and my bilingual-resistant American son