It took me years to master the English language, despite arriving in the States with a fine graduate school education, and even a propensity for foreign languages honed during time spent in Scotland.

It took me years to master the English language, despite arriving in the States with a fine graduate school education, and even a propensity for foreign languages honed during time spent in Scotland.

The challenge wasn’t about understanding the words, it was about connecting with them. How to feel the meaning of empty terms in a new language that I didn’t inhabit yet to bring them alive. Only time, living in the U.S. and growing in the culture that produces its idiom could teach me that.

And so, when author, college professor and globetrotter Tim Brookes created Endangered Alphabets, an itinerant exhibit to preserve both the syllabaries and the civilizations they represent, I knew why his project was meaningful.

Words and their symbols speak of the soul of a people. “Lose them, and we lose ourselves,” says Tim in the poem he wrote for the venture.

The impetus arrived in 2009 when he discovered that one third of the world’s 100 alphabets, which account for 6,000 to 7,000 languages, may disappear by the end of the century.

“I decided to carve a few to preserve them in a rather more solid form, and draw attention to the issue.”

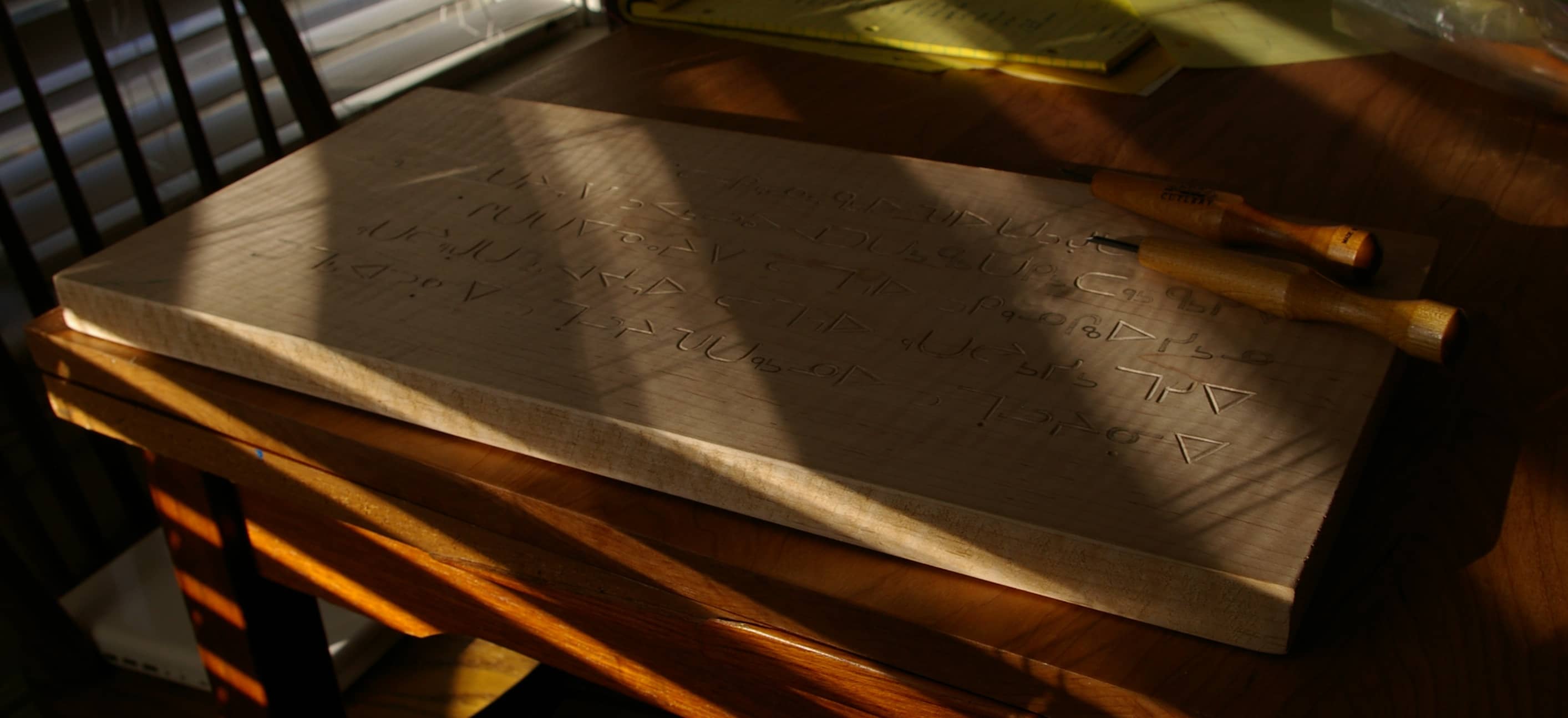

The exhibit, which has grown since it first started, comprises of over 20 hand carved Vermont curly maple boards. Each features an endangered alphabet and its version of Article One of the United Nation’s Declaration of Human Rights. Balinese, Bassa Vah, Baybayin, Bugis, Cherokee, Inuktitut, Khmer, Mandaic, Manchu, Nom, Tifinagh, Pahauh Hmong, Samaritan and Syriac, are among of the syllabaries represented. (See photo)

Aided by an international following of scholars and supporters, Tim, a longtime Vermont resident born in England, has traveled to Oklahoma for Cherokee, and as far as Bangladesh to carry out field research for the exhibit.

Q and A with Tim Brookes

How did an English man, of all people, decide to undertake such project?

The English have an odd role in all of this. [They] can be ridiculously provincial, yet (perhaps in reaction) some Brits have led the field in exploring other cultures and other languages. [Lady Ethel Stefana Drower], the principal expert on the Mandaean people in the Middle East, was one of those fearless English explorers who went where no outsider, male or female, had been allowed.

I just found it all fascinating, and the fact that I’m pretty well traveled, yet had never heard of most of these languages or scripts, made it all the more compelling.

Why are so many alphabets becoming extinct?

In many cases, they are scripts used by an ethnic minority repressed by the government. In many others its simply the cultural imperialism of the West and the Internet: if you use a computer, you’re far more likely to use the Latin alphabet and a standard keyboard.

Can that be stopped?

The Cherokee are making heroic efforts to teach their children the Cherokee language and syllabary, but even then those same children will have to undertake standardized American testing in schools, using the English language and the Latin alphabet. To retain their identity they have to be bilingual and biscriptural.

What’s the role and meaning of the Endangered Alphabets book?

As I was carving the boards, I developed the hypothesis that I would learn something about each script, each language and about writing itself just by doing the carving. It turned out to be true, and as such the book is also an investigation of the nature of writing.

Let me give you an example that isn’t actually in the book, of how carving led to thinking. [A few nights ago] I put a coat of polyurethane on a piece of Vermont tiger maple that has two (literally) overlapping visual characteristics. One is the Balinese character for Om, an astonishing piece of graphic art that looks like a cat wearing a crown. The other is the ripple in the grain, which is so strong it looks like a three-dimensional hologram of the isobars of a monsoon.

What struck me, as I looked at one pattern floating above the other, was that a human pattern was overlaid on a far older, natural one. Language [too] is all about pattern recognition: we hear sounds or see symbols and recognize them, thus ascribe meaning. No recognition, no meaning.

That carving suggests that we have inherited our understanding of pattern, and thus of language, from patterns as old as the planet, as old as physics, that rule everything around us. That one board spells out the history of the universe, and of our human attempt to ride out those stormy currents by establishing patterns of our own.

That’s the kind of reflection that turns up in the book, which basically chronicles the carving-and-thinking process and goes down all kinds of fascinating avenues I had never thought about before.

What do alphabets say about a language, a culture and the spirit of their people?

Let me give you an example. Balinese and Javanese are virtually the same script, but every letter in Balinese is executed with a flourish and a swoop that takes mere handwriting and elevates it to the quality of art. Something you’d expect from a nation with such a tradition of music and dance.

Our Latin alphabet, by contrast, is all about architecture: each letter is solid, balanced, dependable. Many are symmetrical. It’s an alphabet that was chiseled, then mechanized. Compare that to Samaritan, which looks like a thicket of thorny twigs, or Balinese, which looks like a flock of birds and you’ve got to believe that the way we write says something about the values we espouse.

How long did it take to put together the itinerant exhibit?

The initial exhibition of 14 pieces took about 11 months; since then I’ve added several more pieces and another half-dozen alphabets. The hard part was finding someone who could still read and write these scripts. I got one [at the beginning of October], the utterly mind-boggling Dongpa script for the Naxi language in China, that has been on my wish list for two years.

Where have you taken it?

So far the exhibition, which travels in a wonderfully battered trunk that was previously owned by a diplomat, has been throughout New England and down to New York, visiting colleges and universities and libraries.

Ironically, the very first booking the Alphabets got was completely different. While I was still carving the initial show and was looking for more pieces of this amazing curly maple, I called foresters and lumbermen and wood products suppliers and the state agriculture department, and the head of the Vermont Forest products Association said, “That sounds really neat. Would you like to display it at our annual show?” So I said yes, of course, and as a result one weekend the carvings were separated into two groupings: one formed a kind of woody backdrop to the Burlington Book Festival, and the other turned up at the Vermont Fine Furniture and Woodworking Festival!

What’s the message that you hope people will take home after seeing Endangered Alphabets?

In general, my hope is to raise awareness of the issue and encourage genuine scholars, not writers-turned-woodworkers, to study the phenomenon.

My personal hope is to set up a World Tour, in which I take these scripts back to their countries of origin. While I’m there, I want to do two things. First, put up the exhibition talk about it, and [cover] the importance of cultural preservation.

Over the next few days, I will track down people who can still read and write the local endangered script, get them to write me out a text and carve it in local wood. In fact, I’d carve two copies, one to give back to them and one to add to the exhibition as it moves on.

Tim Brookes is the author of 13 books spanning subjects as diverse as a driveway diary and chasing monsoons in India for National Geographic. For more on Endangered Alphabets and their exhibition calendar visit www.endangeredalphabets.com or contact Tim at brookes@champlain.edu

Print This Post

Print This Post

I’m really fascinated by this project. I’m an artist from Sierra Leone and was researching ancient African scripts when I came across the absolutely beautiful Bassa Vah script and your post. I’ve incorporated it into some of my paintings, a reminder if our lost heritage. …

I just couldnt depart your site prior to suggesting that I incredibly enjoyed the standard information an individual supply for your visitors? Is gonna be back often so that you can inspect new posts

Thank you John, our team works hard to publish new and original content that will uplift and support the lives of our global readers. The Editorial Team