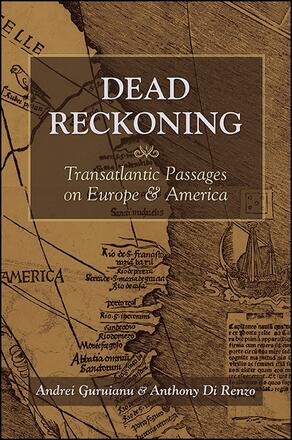

It began as a keep-in-touch note that grew very long and hijacked their creative connection. Two prolific writers, Andrei Guruianu, 34, a Romanian-born poet and essayist who grew up in Queens, and Anthony Di Renzo, 54, his novelist counterpart of Italian descent, embarked on a literary voyage of lost lands and new countries where no map could trace the territory. Out of it came Dead Reckoning: Transatlantic Passages on Europe and America, the epistolary book that wrestles with the overwhelming realities of carrying roots and holding memories, and the holy damnation of freedom when chasing the elusive sense of home.

It began as a keep-in-touch note that grew very long and hijacked their creative connection. Two prolific writers, Andrei Guruianu, 34, a Romanian-born poet and essayist who grew up in Queens, and Anthony Di Renzo, 54, his novelist counterpart of Italian descent, embarked on a literary voyage of lost lands and new countries where no map could trace the territory. Out of it came Dead Reckoning: Transatlantic Passages on Europe and America, the epistolary book that wrestles with the overwhelming realities of carrying roots and holding memories, and the holy damnation of freedom when chasing the elusive sense of home.

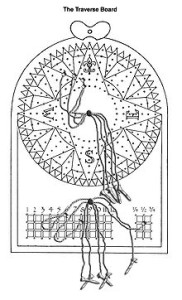

“The title of our book is a nautical term,” said Andrei quoting the preface to the work when asked about the expression.

“[It’s] desperate guesswork. In this sense, dead reckoning can function as an analogy for postmodernism, Europe’s and America’s collective groping in the dark because the West has lost or destroyed its bearings.”

Dedicated to Milan Kundera, the celebrated Czech writer who made exile his muse, the book (still in manuscript) explores what’s universal among people who come from somewhere else in the world to hang their hat in America.

“Perhaps our notes,” the authors concede in their message to the reader, “will become the survival manual for fellow castaways like you.” On the next paragraph, they make a special notation for language, the other parallel cosmos of transplanted lives.

“Please pardon our accents,” they say in unison, “English is not our first language, but it is the language that we are compelled to write in. It baffles us, but as Edvige Giunta, the Sicilian American poet observes, ‘living in another culture and writing in another language sometimes offer an intellectual and creative freedom that living in your own culture and writing in your own language do not’.” Perhaps we need to maintain our foreignness to access and jot these thoughts.”

The conversation takes place during the centennial of the Great War, noted Antonio, Andrei’s co-author, when Western Civilization fell apart. “As we sail into a new millennium, will we repeat the same mistakes?” ponders the writing duo.

The epochal characters they examine (Nietzsche and Rilke, Mazzini and Zamenhof, De Chirico and Ionesco, Mussolini and Ceaușescu) personify the problems and paradoxes of that era. “Their dreams and nightmares formed our world.”

Both Guruianu and Di Renzo are college academics. Guruianu is a Language Lecturer at New York University, and Di Renzo is an Associate professor of Writing at Ithaca College and the author of “Trinàcria: A Tale of Bourbon Sicily,” a historic novel recently published by Guernica Editions.

Andrei Guruianu is a three times Pushcart Prize nominee and his verses have been widely published both nationally and internationally. From 2009 to 2011 he received the title of Broome County, New York’s first poet laureate.

What follows is the edited version of our email conversation about the artistic and existential drive that produced Dead Reckoning, and how the roundabout motions of modern life can make anyone feel lost at sea.

[pullquote align=”left|center|right” textalign=”left|center|right” width=”30%”]“ANDREI: The Eternal Children”

THANKS TO ADVANCES IN MASS TRANSPORTATION, more people are crossing borders than ever before. More people claim multiple homelands than ever before. And, paradoxically, more people feel homeless than ever before. This alienation, however, isn’t always a numb limbo in No Man’s Land. Sometimes it is an agonizing trip to Neverland. (Excerpt from “Dead Reckoning: Transatlantic Passages on Europe and America,” p. 108)[/pullquote]

Q: How did the project start?

It has its roots in an exchange of emails in the summer of 2013 where I would send Antonio several poems I had been working on. To my surprise, and quite a pleasant one, he would often reply with eloquent anecdotes and what I would later call “mini essays.” Antonio is one of the most thoughtful, brilliant, and witty men that I’ve ever met. His replies bear those marks.

We could easily have proceeded this way – I send you a poem and you try and decode it, try to tell the reader what it means. I think that if we had proceeded that way we would have lost some of the unpredictability of the process, the surprise moments that arose from the freedom to make imaginative leaps. Instead, what Antonio did was reply to the intangible in those poems, to an intuition, a personal emotional or intellectual resonance.

Q: Dead Reckoning innovates on the definition of genre by featuring a conversation between two  “borderless” writers that includes quotes, poems and essays. You and Antonio, your co-author, covered a territory that extends from self-reflection to satire. How does this work align with your current aesthetics?

“borderless” writers that includes quotes, poems and essays. You and Antonio, your co-author, covered a territory that extends from self-reflection to satire. How does this work align with your current aesthetics?

My early work was very much “about me,” which I think was inevitable. I had to explore the person I was and the person I happened to be in the process of becoming. So my writing explicitly tried to grapple with issues that would “explain me to myself” primarily. Slowly I’ve been stepping outside of that zone.

To that extent Dead Reckoning contains poems, specifically, that are no longer “about me” and instead “are me.” By removing the explicit “I” I believe the work here transcends the personal and can be considered “global” or “universal” in scope.

Q: For whom is Dead Reckoning written and why?

To be honest, this is probably one of the first projects I completed or wrote primarily for myself.

It was such a rush of excitement exchanging these poems and essays with Antonio that I simply wanted to see what else we could do, what else we could come up with next and where the discussion would take us.

That was initially an extremely freeing realization, that I was writing for my own sake and for my own pleasure. I could say that several of my previous books have been written with audience in mind, but this one did not begin that way, and it was not a consideration until well into the process when we began to talk about editing, order, and overall presentation.

Of course, now it is a book for just about everyone. It is for all those who love art and poetry and writing that gets you thinking. It is I think a book of surprises and one that keeps the pages turning – you want to know what’s coming next, what connections we’re making and where in the world or where in time the discussion will take us.

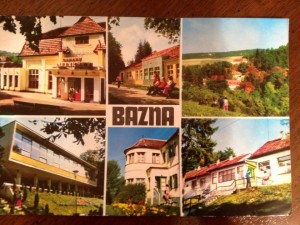

Q: You migrated with your family from Romania to the United States at the age of eleven. How does our place of origin remain active and meaningful within us throughout our lives?

Place dwells in the subconscious. Even when our consciousness is being eaten up or oppressed by whatever might be going on in our lives, our subconscious can dip into that realm where the familiar lives, where “home” exists, and to where we return always in our dreams or whenever we need to regain our bearings. Sometimes the move is intentional, but often I believe we have no choice and are pulled back there by some unseen force.

I think this might serve as a good example of the unpredictability of these forces. My own mother, after reading a story in my latest collection titled Body of Work, asked if the segments about the Black Sea (where we spent many summer vacations during the 1980s) were a metaphor for something. She said she had some ideas. I thought, Great! Maybe now you can tell me!

Q: How does postmodernity breed these powerful, yet elusive, inner motions?

I don’t know. I don’t think about labels when I write. If my fragmentary style and topics of disconnectedness and disillusionment, or loss and struggle for direction fit the badge of postmodern then so be it.

Chances are a hundred years from now there will be a different label tacked on to it. All we can do is live and work and write the best way we know how while navigating whatever current sweeps us up in any given moment.

Chekhov said something to the effect of “Artists do not need to have the answer. They have to ask the question.” But sometimes we know neither the question nor the answer. In that regard poetry is indeed elusive and always has been, darting here and there in the dark only to pop out once in a while, show its face and stare you in the eye. It makes the reader ask their own questions, to wonder and get lost and try to find their way back again, the only light leading the way the language on the page.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Comments for: When The Map Is Not The Territory: Dead Reckoning